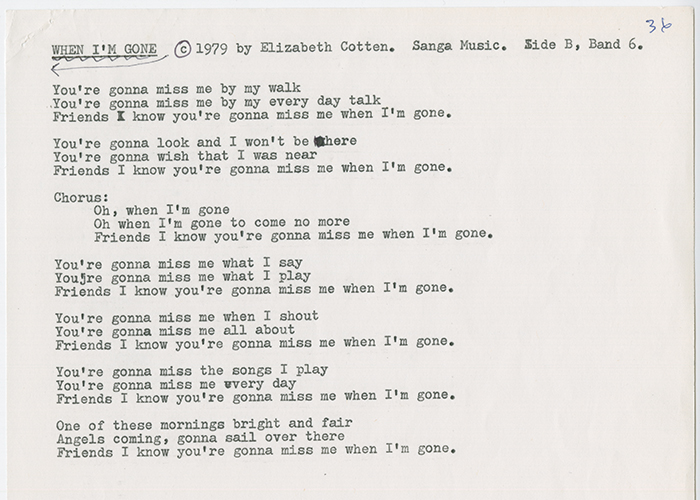

A version of this article originally appeared in the 1968 Newport Folk Festival program book, and then in the 1970 Folklife Festival book.

Have you ever wondered how a person in a community happens to become a good folk musician? After you’ve talked about this with a number of singers and instrumentalists, you find that the process is a fairly constant one, no matter what the type of community, what the size of it, where it is, whether it is black or white.

Perhaps the most common pattern is this: a person grows up in a situation in which there is music made by people he or she knows, perceives music as something you do (rather than sit through), gets occasional use of someone else’s musical instrument and manages to learn some basic techniques, then begins to do a little experimenting, and finally, in the best cases, comes out the other end with a style that is at once in the tradition and expressive of the person making the music, public and private.

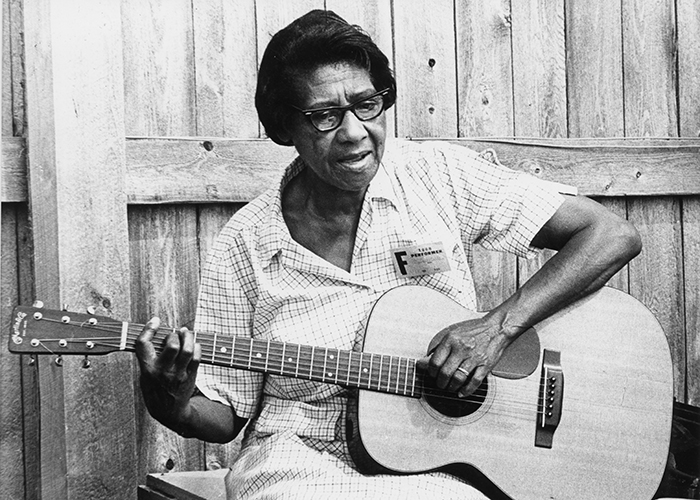

In 1966 Mike Seeger taped an interview with Elizabeth Cotten in the course of which much of this was finely illustrated and illuminated. Libba has been an influence on a wide range of performers in recent years as well as an important member of the folk scene in her own right. One can use the same words to describe her as a person and the music she makes: delicate, gentle, expressive, lovely.

***

My mother’s father had ten children and he was a hard worker. He worked the children very hard. She was the second child, and he just about made a boy out of her. You know, ’cause he needed another boy so bad. He was a man who loved to have plenty of everything. They had cows, horses, plenty of butter, chickens, eggs. Everything that farming people had, he had plenty of it. My mother was raised up on a-plenty to eat but she worked very, very hard for that. My grandfather had a granary, a smokehouse. My grandmother never had to go to the field. She was the housewife.

My father’s people was Indians. My father’s mother was a slave. My mother’s people were not slaves.

What kind of work did your grandfather and grandmother on your mother’s side do?

They were farmers. That’s about the onlyest thing at that time for colored people to do. They didn’t live close nowhere that they could work for nobody. They just kind of had to sow their grains and reap them, ’cause there was no other way to make a living.

I used to hear my mother say she used to go so far to help somebody—to scrub, clean, and churn, and right at that time I don’t think they had a car—and she had one or two kids I’m sure. And they’d give her milk and butter to pay her with, meal, a piece of meat. Money was never involved in it.

I used to hear my mother say how far she’d have to go and come, but she would go. And saying this white lady would be very nice, would always give her a hunk of meat, meal, as much as she could bring—sweet potatoes and all that kind of stuff—home to the children. And she’d go and work near about all day for that.

After we came to Chapel Hill, my father worked in a mine. It must’ve been a iron mine, I guess it was. That’s the onlyest thing I reckon it would be in Chapel Hill. And my daddy he was the dynamite setter.

My father was a man. He never wanted a easy job. If somebody offered him a easy job he’d say, “Oh, that’s a boy’s job.” He wouldn’t take it. He liked a hard job—looked like he worked very hard. If he didn’t he felt like he weren’t a man or something. My father was very tall, kind of a raw-bone man. What I mean by that, he wasn’t fat. He was big bones, gray skin, beautiful hair, and his hands was nice and thin, he had nice thin foot. But he wouldn’t take no easy jobs.

When my brother left home I didn’t have nothing to play—nothing to pick, rather—no strings. So I wanted me a guitar.

I wasn’t twelve years old, and I goes to work for this lady. Her name was Miss Ada Copeland. I’d give anything to find those people again. She paid me seventy-five cents a month. She said I was very smart. I was a lot of help to her. The kids liked me; she had two children, a boy and a girl, and sometimes they’d cry when I’d leave to go home. So she said to my mother, she says, “We’re going to raise little Sissie’s wages,” says, “we’re going to give her more money.” So they gave me a dollar a month, twenty-five cents raise. That was a pretty good high raise, wasn’t it? And if you think about it, it sounds like a little money, but in them days for a child not twelve years old, if you think about it, it might’ve been a good price. I don’t know. My mother was one of the top cooks in Chapel Hill, one of the best, and she didn’t make but five dollars a month.

But anyway, I saved my money and bought me a guitar. Only one place in Chapel Hill at that time you could buy a guitar. That was Mr. Gene Kateshe’s there yet. I think the store is in the same spot. And my mama carried me there to buy this guitar. So he says, “Aunt Lou, bring your little girl back tomorrow and I’ve got the guitar I think is for her.” Went back the next night and sure enough, there was my guitar. I knowed it was mine laying on the showcase. So he says, “Well, Aunt Lou, I got your little girl a guitar.” And she says, “Well, Mr. Kates, I don’t know how.”

She thought it was going to be a whole lot of money, I reckon. She says, “I don’t know whether I can get it or not. How much money is it, Mr. Kates?” He says, “Aunt Lou, I’ll tell you the truth, as long as you and your little girl wants a guitar as bad, you can have it for $3.75.” And Mama had that much money of mine where I’d done worked I don’t know how many months for it. And the name of that guitar was Stella. And I liked my guitar so very, very much, and that’s when I began to learn how to play a guitar.

Is that the first guitar you ever played?

My first guitar.

You’d only played banjo before.

Banjo. My brother had a banjo.

Can you remember what kind of style you played first?

The first thing I’d do, I laid the guitar flat in my lap and I worked my left hand ’til I could play the strings backwards and forwards. And then after I got so I could do that, then I started to chord it and get the sound of a song, a song that I know, and if it weren’t but one string I’d get that. Then, finally, I’d add another string to that, and kept on ’til I could work my fingers pretty good. And that’s how I started playing with two fingers. And after I played with two fingers for a while, I started using three. I guess all that was learning me how then, I was just trying to see what I could do. I never had any lessons, nobody to teach me anything—I just picked it up.

After I bought Stella, I wasn’t too long learning. I played all the time. My brother used to play, but he didn’t play like me. And the friends of his that owned guitars and come in there to play, they didn’t play like me. I didn’t hear nobody picking no strings. They sang to the music and made chords. My brother played very, very pretty. The strings would just say what he was going to sing.

And then when I started my finger picking, his friends sometimes would come over to play with me. I was always the leader, and they’d play like my brother played: behind me. I would lead the song and then they would, what you call it, strum. They didn’t pick it. And they used to say to me, “Sis, how in the world do you get your fingers to pick all them strings?” Well, I wouldn’t know.

I just loved to play. That used to be all I’d do. I’d sit up late at night and play. My mama would say to me, “Sis, put that thing down and go to bed.” “Alright, Mama, just as soon as I finish—let me finish this.” Well, by me keep playing, you see, she’d go back to sleep and I’d sit up thirty minutes or longer than that after she’d tell me to stop playing. Sometimes I’d near play all night if she didn’t wake up and tell me to go to bed. That’s when I learned to play, ’cause then when I learned one little tune, I’d be so proud of that, that I’d want to learn another. Then I’d just keep sitting up trying. I tried hard to play, I’m telling you. I worked for what I’ve got. I really did work for it.

And then you dropped the guitar for a while?

I did on account of religion. When I was in my teens I got religion on that song you hear me play, “Holy Ghost, Unchain My Name.” And I was baptized. The deacons, if any of them people see you or hear tell of you doing something that’s not Christian, they would report it at the church. So they told me, “You cannot live for God and live for the devil.” If you’re going to play them old worldly songs, them old ragtime things, you can’t serve God that way. You’ve either got to do one or the other.”

Well, I got to thinking of it, I got religion, I joined the church for better, and I want to do the right thing. I didn’t stop all at once ’cause I couldn’t. I loved my guitar too good. I just gradually stopped playing. And then it weren’t too long ’til I got married. And when I got married that helped me to stop because then I started housekeeping, and then it weren’t too long before I had a baby.

My baby and my housework and my husband, I loved that so much, until I just kind of drifted away from the guitar. I just didn’t do it much. And then, to keep from going out to work and leaving my baby, I taken in washing and ironing at home. Had about three families’ wash that I’d do at my home. And by doing that, and my cooking and taking care of her, I was busy.

I just forgot about the guitar, and to tell the truth I don’t know what happened to the guitar. I’ve tried to think. I don’t know whether it was left or whether somebody borrowed it. I don’t know what happened to that Stella.

I came back to Washington years later to be with my daughter when her baby was born so I could take care of the family. I applied at Lansburgh’s Department Store for work before the holidays. That must have been in ’47 or ’48, and they hired me, and they give me a job up on the fifth floor with the dolls. They couldn’t have pleased me no better in the world.

Mrs. Seeger came in the store. She bought two dolls from me and a little lamb. I think the little old lamb, it laid around for the longest time. She brought two girls with her. While the dolls were getting wrapped at the counter, Peggy wandered off—she was the oldest little girl with her—and she got lost in the store. So me and her other little sister was running around to find her. And I found Peggy, she was crying. Course tears came in my eyes ’cause the child was crying.

Then when I brought her back to her mother, her mother says to me, “Have you worked here long?” and I told her, “No.” And she says to me, “If you ever decide to stop working here, here’s my telephone number—give me a ring sometime.” I told her, “Yes, ma’am, I’d be glad to.” But when she came in the store I just said within, “Now I would love to work for that lady,” not knowing I was ever going to work for them.

So when I stopped working for Lansburgh’s store and decided to look for work, I did call her, and so I took the job to give them lunch on Saturdays and dinner plus the other work I was doing.

From the Moses and Frances Asch Collection, Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives

And she had all kinds of instruments around there—guitars, two pianos. So when she’d go in to start her lessons, I’d get Peggy’s guitar and go into the dining room and play myself a little tune. So I was there playing one day and Peggy and Michael overheard me and they said, “Why, Elizabeth, we didn’t know you could play a guitar.” Well, I was standing with the guitar and nothing for me to say. I just played the guitar.

Peggy said, “That certainly was a pretty song, would you play it for me? Would you learn me how to play that?” So then I started learning Peggy how I know to play it, and she wasn’t very long picking up “Freight Train.” And then I showed Mike; he played “Freight Train.” And when I knowed anything the two of them could play the same songs as I could just like I played them.

And that was my first guitar between all that time. I don’t know how long it was, but it was a long time. And that guitar, the lost child at Lansburgh’s store, is what made me what I am today—a “Freight Train” picker. That’s the truth.

Mike Seeger (1933–2009) was a folk musician and folklorist who grew up in the care of Elizabeth Cotten, along with his sister Peggy. He recorded music for Smithsonian Folkways as a solo artist and as a member of The New Lost City Ramblers.